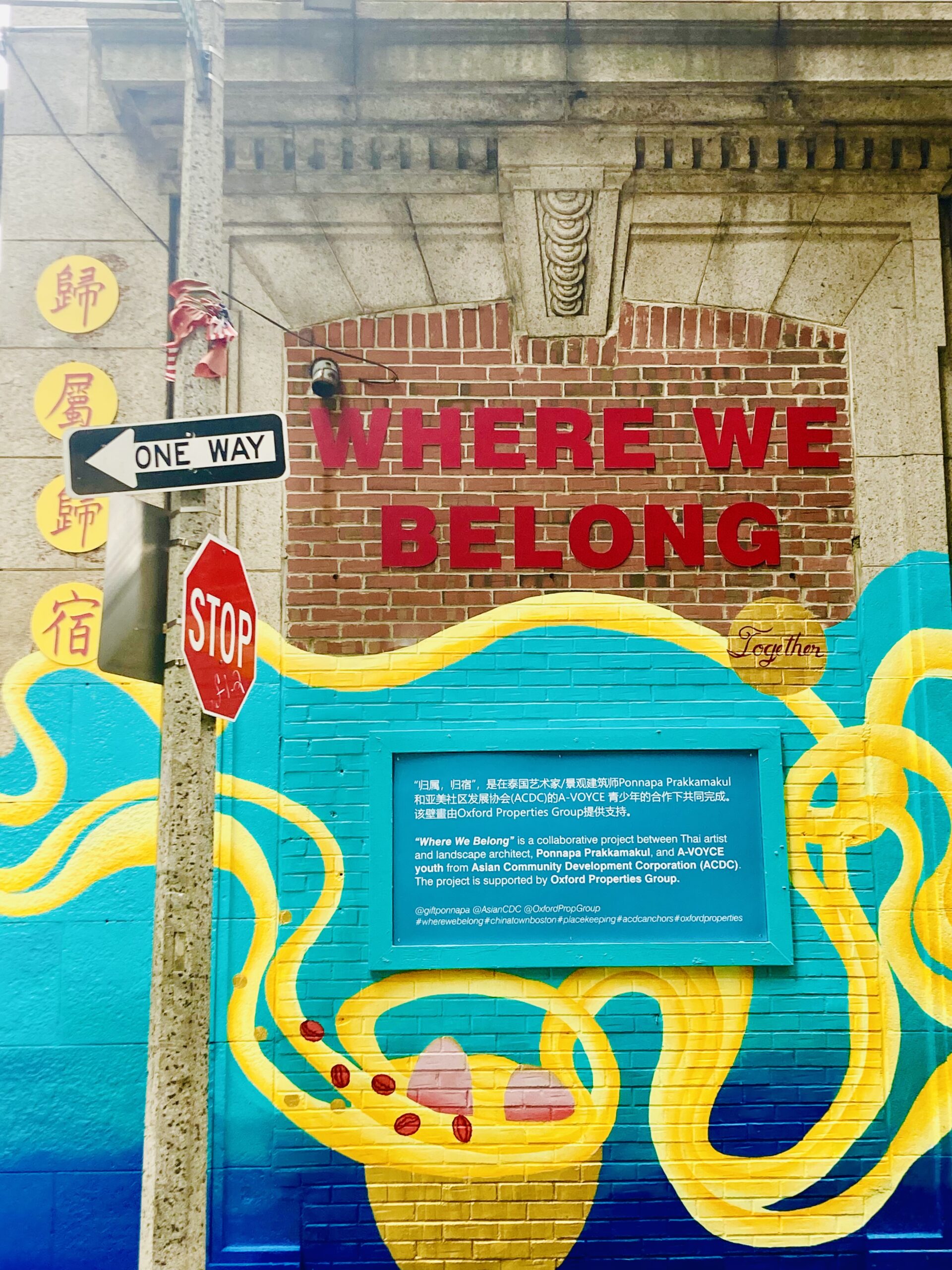

Over a year ago, what used to be grey concrete turned to gold – a radiantly colorful mural unified a community of local residents, visionary youth, vulnerable unsheltered people, and more through an amalgamation of dancing noodles, a majestic dragon, illuminated candles to both celebrate birth and as a vigil to honor those who are gone, and a dialogue of languages tying us together to bring us home. In a span of a few weeks, Ponnapa Prakkamakul, an award-winning multidisciplinary artist and landscape architect, painted the 150-feet exterior wall and the front door of the once Ho Toy Noodle Company on Essex Street in Boston’s Chinatown in partnership with the Asian Community Development Corporation (ACDC).

When ACDC was asked about their partnership with Ponnapa as an artist for this project, Angie Liou, the Executive Director of the Asian Community Development Corporation, stated, “We knew from the beginning that we wanted to engage a visual artist that had an immersive style to reflect diverse voices and experiences. Ponnapa uses the painting process as a tool to experience, understand, and connect with her surrounding environment. She shared our vision that the mural would embrace and illuminate Chinatown’s traditions and cultures, strengthen the community, and give voice to themes that matter to residents…. Ponnapa had also worked with ACDC’s Residence Lab years ago, where she worked closely with our immigrant residents to co-create temporary art installations [called Sampan], so we were confident that she knew how to work with community members and youth and get input from them that would inform her work.”

The Asian Community Development Corporation has been working in underserved and immigrant Asian-American communities in Greater Boston, Malden, and Quincy, by building affordable homes and vibrant spaces, empowering families with asset-building tools, and strengthening communities through resident and youth leadership and civic engagement. In reflecting of their hope for the community with this mural, ACDC’s Angie stated, “This beautiful artwork by Ponnapa will undoubtedly start new conversations about what Chinatown means to the working class immigrant residents here; we also hope it will uplift and connect our community after a particularly tough year [of 2020]. As the Chinese name for the art mural reflects: 歸屬,歸宿 “gui shu, gui su” – the first part means to belong, or a sense of belonging, and the second part means home, a place to return to, or a destination/support. We believe that this mural will help call people home to Chinatown.”

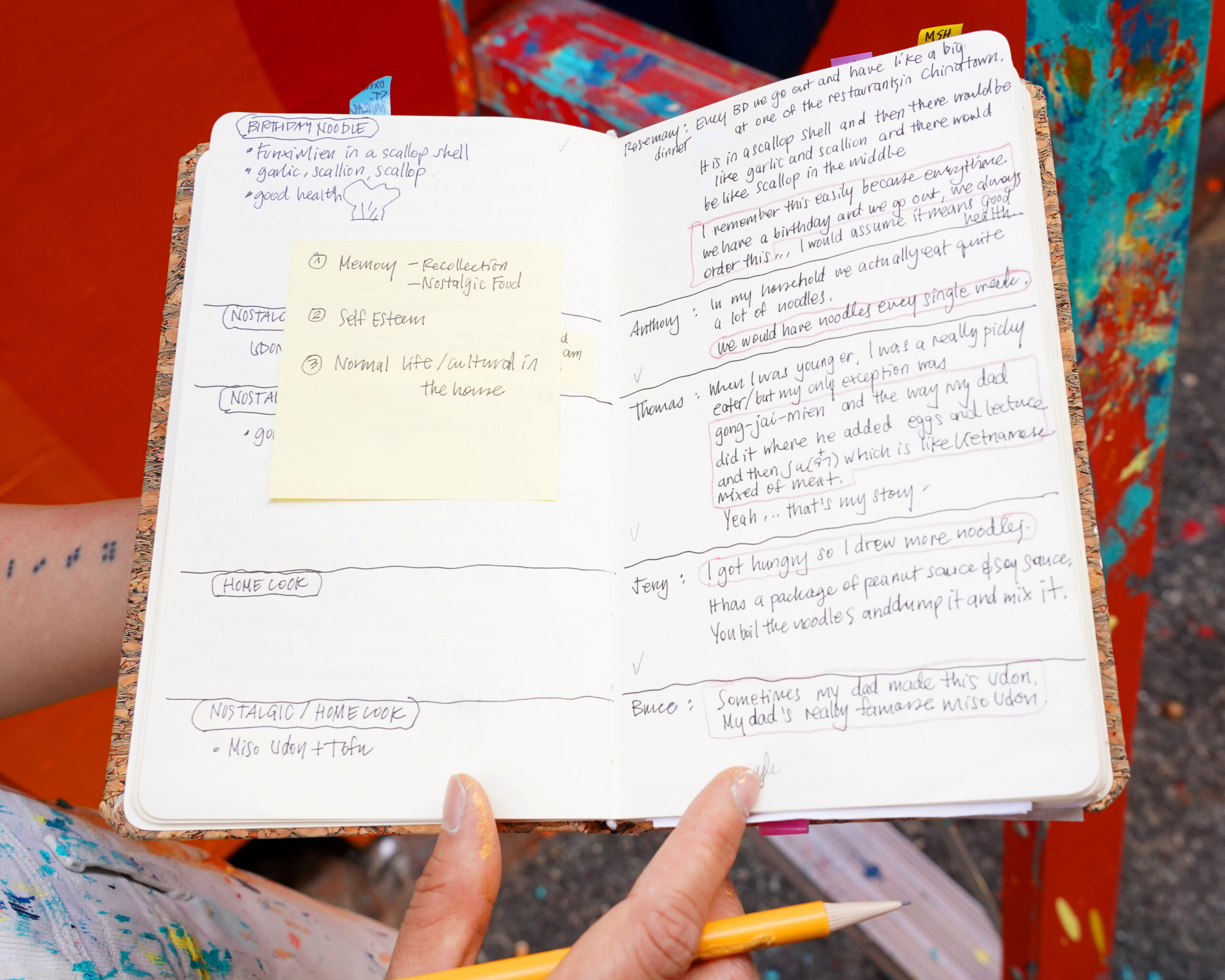

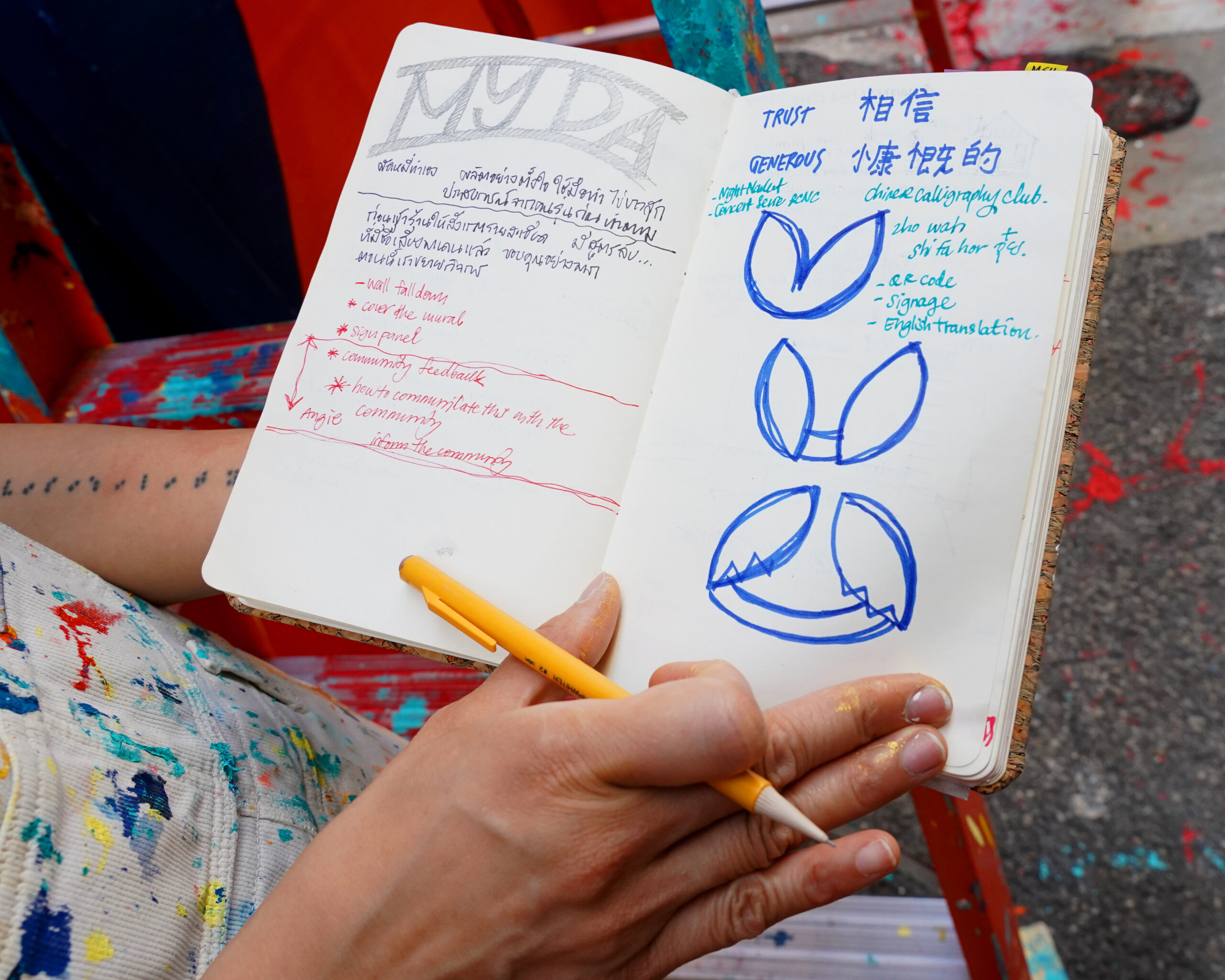

To begin the process of this project, Ponnapa held brainstorming co-creation workshops with the youth from Asian Voices of Organized Youth for Community Empowerment (A-VOYCE), which is ACDC’s youth leadership program within Greater Boston. The intention was to involve the voices of resident families through working with youth leaders of A-VOYCE. She posed a series of questions and prompts for the youth to engage them in their own familial and ancestral storytelling. When she asked the youth to ponder on what their superpower might be if they could magically have them, one of the teens said, “I would have the superpower where I could convince the rich people to give money to the poor.” This brilliant thought process from the youth entwined with the mural of flowing noodles gives new layers of meaning to French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s infamous phrase, “Eat the Rich,” which is now often used to address the class struggle and atrocities created through racist capitalism.

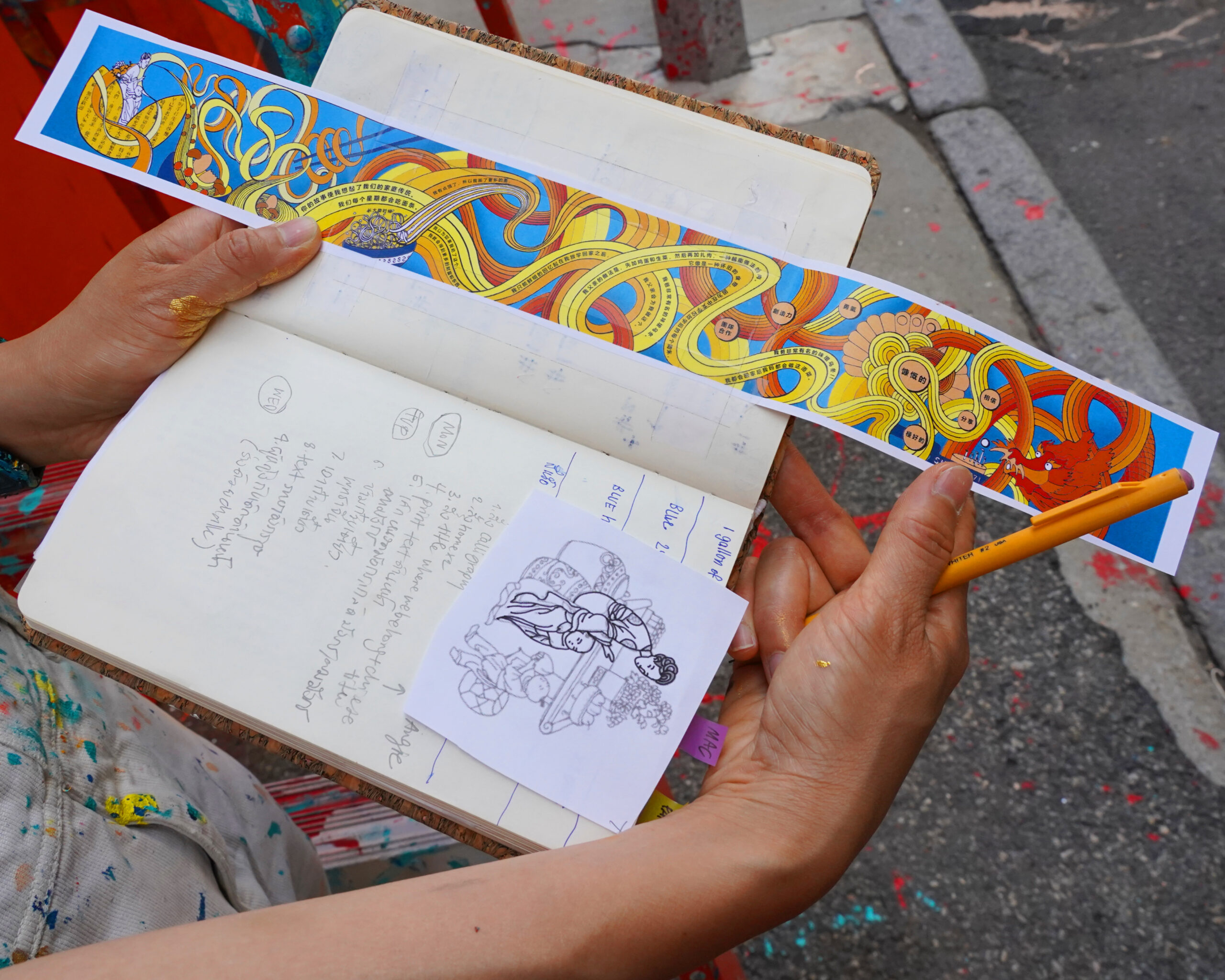

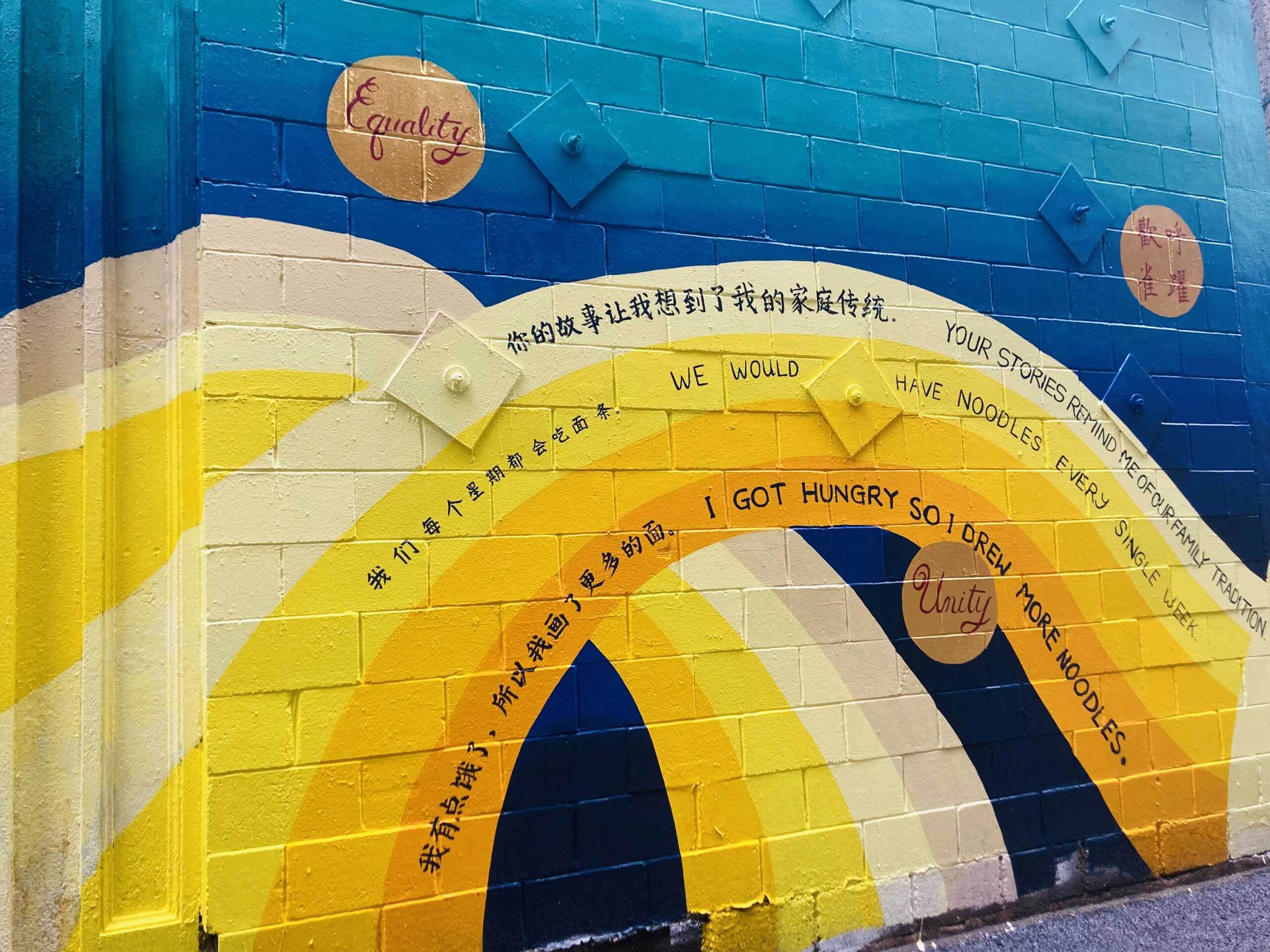

Much of the youth’s conversations centered around the ongoing gentrification and wealth disparities of the inner-city Boston neighborhoods in juxtaposition with Greater Boston’s privileged neighboring towns. Through this community dialogue, the teens also realized that despite the diasporic differences and lack of resources, they still had so much in common through their cultural traditions, their learning and unlearning of their ancestral native tongue, and sacred flavorful noodles to remind them that they are not alone. Ponnapa drew inspiration from both the youth’s reflections and suggestions as well as her own personal background as a Thai artist whose family migrated from China to live in Thailand. She then went on to live in Hong Kong, and now in U.S.A. to share her own unique immigrant experiences as a Chinese-descendant Thai artist living in various colonized lands.

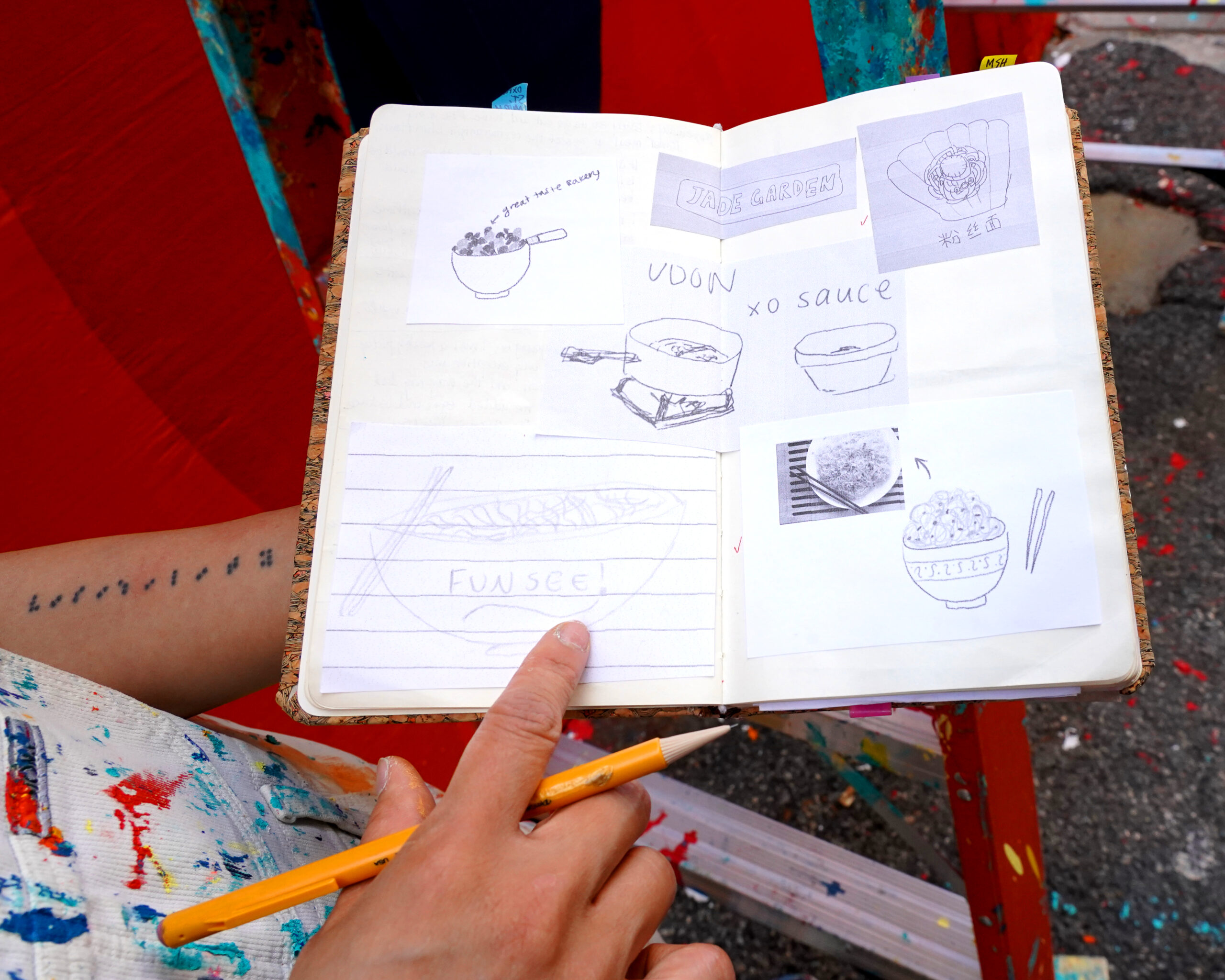

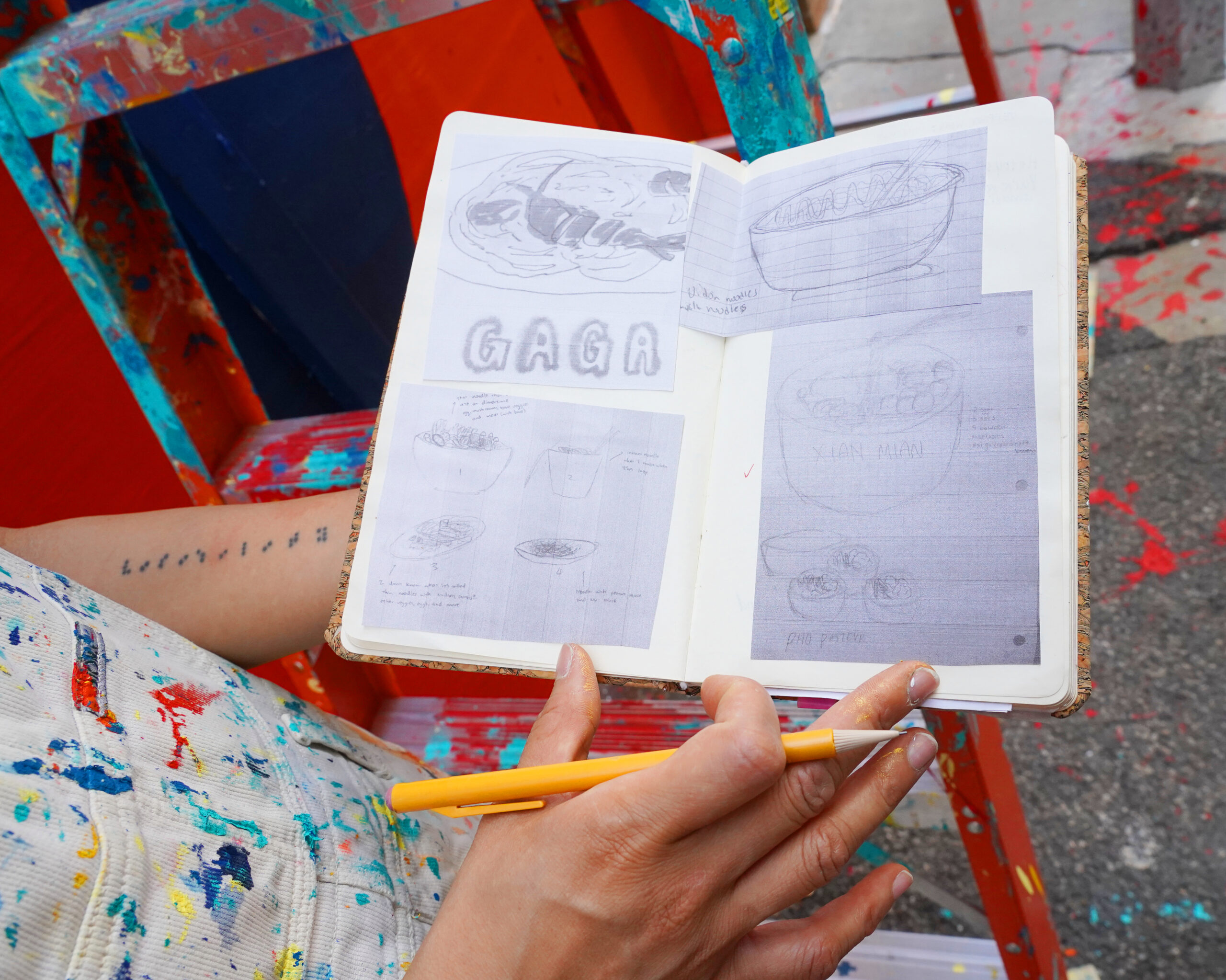

Being a South-Asian immigrant myself, I have found that most people often don’t realize that immigrants and children of immigrants carry only pieces of their cultures with them, sometimes desperately trying their best to hold on to and preserve what they can, sometimes washing away parts of them in shame or sadness endured from living through others’ prejudices, and mostly always longing to define a sense of home – something to call our own with a hope of belonging, even if its just to ourselves. In order to honor all the different stories and perspectives, Ponnapa spent time in meticulously researching the history of Ho Toy Noodle Company and accurate Chinese phrases to design the most relatable and community-building artwork. Her notebooks are filled with astounding details to capture every tale, which can breathe new life into those walls and street. Below are images of her notebook pages, as well as Ponnapa with the in-progress mural, the eloquent imagery and writing on the wall, and some volunteers who came for a day to help paint the Chinese lettering. The volunteers are Ponnapa’s colleagues from Saski who decided to support her for a few hours as their workplace is adjacent to the mural. Ponnapa spent several weeks painting this mural as it took on a new life for her in all that it could hold.

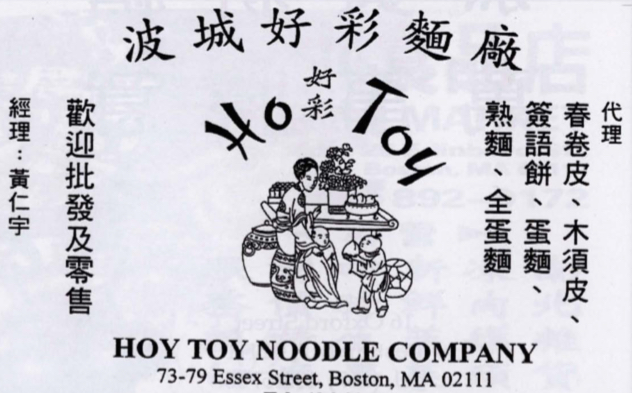

During the process of painting this mural, Ponnapa realized that the aspects of its structure can be a teaching tool for families. One mother pointed at the old public telephone booth to explain to her child that this device was once used before the age of cellphones – what could easily be looked at as a nonfunctional eyesore has become colorful history. Keeping in mind the importance of preservation, teaching-tools, and accuracy, Ponnapa took to heart when a local resident pointed out that the script on the door was hard to understand due to some missteps, so she started all over again and repainted the entire door with consistency to linguistic details. Ponnapa spent an hour with the local resident to learn the correct presentation (despite the possible typos in the original writing). The door front reads Ho Toy Noodle Company’s community mission and slogan: “We are now supplying our world-famous handmade noodles, cooked and uncooked, to the restaurants in the Chinese community. Together, we can serve more happy customers!”

The Ho Toy Noodle Company, which was once located on Essex Street around the corner from Boston’s Chinatown Gate, is now located on Harrison Ave in Boston, MA and in Stoughton, MA. The above two images of the logo are from a community pamphlet and the company website.

An elderly local resident reads the Chinese writing on the wall while on his way home.

While speaking with some local residents, Ponnapa heard many stories of the company’s beloved owner, Jeffrey Wong, who created a strong sense of community with his work years ago. While she never met him, his son did stop by and admired the artistic innovative restoration of the store front. In Jeffrey’s honor, Ponnapa painted a dragon lighting the candles of 1970 (the year of the family-owned store’s establishment) as a symbol of the company’s birth and the red dragon representing Jeffrey Wong who is their local supporter and public figure in Boston’s Chinatown. Much like the complexities of noodle dishes with their layers of flavors, there was also destructive practices within the U.S. government in the 1970s. While Chinese ambassadors tried to reunite international diplomacy with the U.S ambassadors, the U.S. government bombed Cambodia, causing another fear-based rift for China. So one could look at these candles both as honoring the birth of a community and mourning the loss of so many lives due to U.S. neo-imperialism and racism.

More so, while painting the mural, Ponnapa reflected on the different practices amongst the various Chinese communities – while growing up in Thailand, she was raised with the tradition of using red in writing for tombstones, but amongst Chinese-Americans “red” is a revered color indicating auspicious occasions. The youth insisted the color red be used in the title of the mural. Again, the duality of life and death toil with one another, especially in the wake of the 2021 shooting of Asian-American sex-workers in Atlanta, Georgia.

For Ponnapa, the intention is that people recognize the multifaceted elements of the mural, where in one angle people assume it’s the ocean with the ebb and flow of the waves or a rainbow in the sky, whereas others will notice the bowl of noodles, and then there is the roaring red dragon. She said, “If people step back and see everything, they will realize that everything is the same thing and connected.” She reflects it back to the anti Asian-hate campaigns proactively at the forefront during that time, and widely acknowledged by society and the media then – where she said that people assume it’s one specific event or person or time period, but it is important to step back and understand its vast reality and all the different perspectives which come into its stories. Ponnapa’s extraordinary mural was sometimes condensed into one layer of truth: a stand against Asian-hate. A body of work standing up for justice is beautifully significant, however, her mural is so much more than just that – while the media and news outlets jump from one “hot” topic to the next within months, from the horrific police brutality among the Black community, the painful anti-Asian hate crimes, the massive death counts from Covid-19, the disheartening mass school shootings, the gruesome oppression upon Palestinian lands and its people to the outrageous overturning of Roe v. Wade with the stripping of people’s body autonomy & reproductive rights and more. Each movement gets a mere couple months of acknowledgement, attention, and hot press. It is important to note that each of these struggles have been present for decades, for centuries.

Racism against the Asian-American community didn’t began with the Covid-19 pandemic, much like police brutality didn’t began with the murder of George Floyd. The U.S. government passing an anti-Asian-hate crimes bill isn’t an offer of support for justice, but rather both an attempt to track down undocumented immigrants and a complete erasure of the brutal oppression upon the Black and Indigenous communities. The Asian community will not be white America’s model minority as many of us stand in solidarity with our QTBIPoC siblings and their struggles. This mural reflects not only the Chinese community, but utilizes Chinese traditions as a catalyst to showcase the joys and challenges of all working-class communities of color, all disenfranchised immigrants, all cultural differences and similarities. Thus, this acrylic-paint-based mural, Where We Belong, lives on to tell a thousand different tales, each perspective offering a growth mindset, transcending time and place.

The Boston’s Chinatown Gate, which is right around the corner from the Where We Belong mural on Essex Street, was gifted by the Taiwanese government in 1982, and its two engraved Chinese writing reads Tian Xia Wei Gong, which translates as “everything under the sky is for the people,” and Li Yi Lian Chi, which represents the four societal bonds: propriety, justice, integrity, and honor. This land is for the people, for all the people. This stolen land of so-called U.S.A., stripped from various Indigenous communities, built from the ground up by enslaved African people and exploited Caribbean, Latinx, and Asian people – this land belongs to all of us.

This collaborative project’s aim was to address the ongoing gentrification, the disparities, and disenfranchisement Boston residents face with the increasing housing costs. Due to the housing crisis happening in major cities, especially in Boston, houselessness has been on a rise. The living conditions of the unsheltered community during the height of the pandemic has been extremely gruesome. According to the city’s annual census, there has been more than four thousand people (individuals and families) unsheltered in Boston, MA.

With the unoccupied storefront, Essex Street in Chinatown had become known to bring in a influx of houseless people struggling with both mental unwellness and substance misuse as their coping mechanisms. During the height of the pandemic, many stores denied access to restrooms to houseless people (which has been a common practice even before), and with the lack of the city’s accommodation for public restrooms, many unsheltered people often used spaces that seemed abandoned to alleviate themselves. When Ponnapa begin the the process of painting her mural, she recognized the challenges faced by the local unsheltered community members. It also became a learning point for her as an artist working on the street, to understand the different circumstances and conditions people endure. Seamlessly, in continuing her daily work with the mural, she witnessed a sense of honor and integrity which the Chinatown’s Gate emphasized upon: she noticed a man unzip his pants to alleviate himself, but then realized he was urinating into an empty bottle as to protect, honor, and show respect to her mural and her work as an artist. Only the empathetic heart can understand the pure beauty of that raw moment.

Along with connecting with various local residents with different opinions and perspectives and the unpredictable mental imbalances of some of the people who misused substances on that street, Ponnapa learned deep lessons on what it took to be a street artist. While she had always been an artist in supervised environments, it was the first time being out of her comfort zone where she understood how important communication, empathy, and understanding others can be as a street artist. She felt admiration for the work and efforts of street artists and their everyday skills.

What is significant to also note is that in this society, many graffiti artists’ work is looked upon as vandalism – only when the art industry gives them clout and recognition do these artists get recognized as street artists. Even amongst the unsheltered community, there are many artists trying to express the pain of their living conditions. Many people looking for housing support are families who have lived in Boston for decades, for generations, now facing homelessness and bounced around from often crowded, unhygienic, rat-infested shelters. While others are forced to live on the streets due to shelters reaching their capacity. It is easy to evacuate them and claim they are causing disturbances in the streets or in neighborhoods, but where is the sense of justice and propriety for them?

It’s important to recognize that much like Ponnapa’s title for her mural, Where We Belong, this is where the unsheltered community belongs, where the people misusing any substances or suffering from addiction belong, where those struggling with mental imbalances belong. We are not so different from one another – just a matter of stepping back and looking at the larger picture of it to understand the vast reality of the interconnectedness of our human living conditions.

Boston, which was once the land of the Wampanoag and Massachusett people and later a blend of various cultures and ethnicities, is growing into an impetuous playground for the wealthy white yuppies and affluent corporations. Chinatown, Roxbury, Dorchester, Jamaica Plain, and other neighborhoods have seen the rise of gentrification as corporate developers are bulldozing through what was once their homes, what once belonged to them, and the various memories of their unique cultural traditions. With art as a catalyst for positive change, the hope is to bring the neighborhood back to the working-class and under-resourced communities.

Ponnapa and the youth of A-VOYCE chose specific sentences in English and Chinese to amplify their memories of personal traditions at home and in their neighborhood in order to shine a light on both community change and togetherness. The Chinese phrases are more attuned to their culture while the English sentences are more general and relatable to all passersby, like “Your stories remind me of family traditions” and “I got hungry so I drew more noodles.” Ponnapa appreciated that the mural took on the life of a museum, where people walked more slowly when passing the mural, reflecting on the art, reading the phrases – it became a conversational piece with their friends and family members. What was often a walk of silence when people used Essex Street as a shortcut, now invited fond rumination of childhood stories and visceral memories. Ponnapa’s mural truly exemplifies the power of art and language.

Ponnapa Prakkamakul is a gentle powerhouse of an artist who often accomplishes so much in so little time. Her dedication, kindness, and openness allows her to create from the most authentic perspective – a year later, this mural lives on to tell more stories, creates a new sense of home for Chinatown’s residents, and brings in layers of flavorful memories mixed with sweet gestures, salt-laced paradox, bitter truths, sour realties, and spicy joy.

She went on to work on many other city wide and personal art projects. Most recently, Ponnapa won the Best in the Show award during the Mayor’s Arts & Culture’s Fay Chandler Emerging Award & Ceremony in a juried exhibition of selected artists. Her mixed media painting called “Because It’s There” (on the left) and other selected artists’ work are showcased in the Boston City Hall’s Scollay Square Gallery till October 30th 2022.

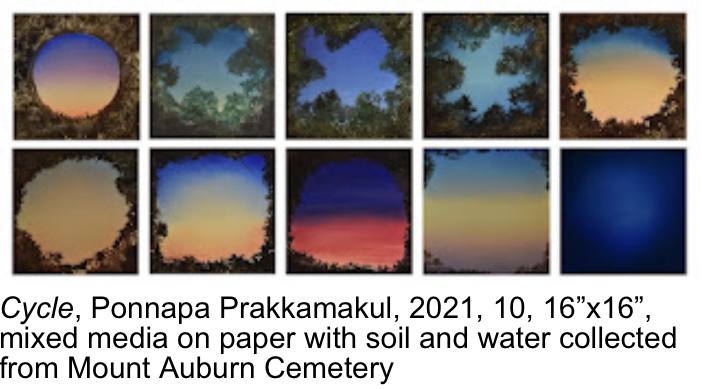

She also has a solo exhibition called “Season of Changes” starting on November 2nd, 2022 at Kingston Gallery in Boston, MA. In a poignant parallel to the mural, Ponnappa’s exhibition Season of Changes: Vatta reflects the impermanence of of the body and mind. Vatta is a Pali word for the “cycle of birth, death, and rebirth.” The work is attributed to predominately her time at the Mount Auburn Cemetery’s artist residency program where she focused on the teachings of Buddhism and the connection of the external natural landscape and the internal works of the human body — both connected with their shape-shifting forms to create a harmonious relationship. Upon walking into the Kingston Gallery, you are immersed in an array of colors dancing to different shades of hues to see the twists and turns that nature endures – we are nature as we return to the ground upon our deaths, so viscerally present in the cemetery. To see the exhibition and hear the Ponnapa discuss her work, please attend the artists’ talk on Thursday, November 17th, from 7pm at the Kingston Gallery. On the right is one of her pieces from the exhibition and a flyer for the artist talk. Please RSVP for the in-person discussion here. And a virtual viewing is available via Live Instagram through @kingstongallery.

In understanding and learning about the process of Ponnapa Prakkamakul’s techniques and methodology utilized in her paintings, especially with the mural Where We Belong mural, one is engulfed with layers of storytelling and a landscape for pure humanity and raw tenderness.

Photography by Nicolas Hyacinthe

*** Disclaimer: All general political and artistic views presented in this article are written from the lens and perspective of the writer / mixed genre editor and does not reflect the views of the artist nor the partnering organizations.